Table of Contents

The Mauryan Empire, spanning from 324 to 187 BC, is one of the important era in

Ancient history.

Major characteristics of Mauryan Empire

- Large area

- Uniform Administration

- External contract

- Ashoka’s Dhamma

- Art and architecture

- Different sources

Sources of Mauryan Empire

From 324 to 187 BC, the Mauryan Empire existed, and it was a significant period in ancient history. There are a lot of primary sources from this era that help us understand the Mauryan dynasty. Of these, the Puranas—particularly the Vishnu Puranas—offer in-depth narratives of the thirteen Mauryan kings, who governed for roughly 137 years.

Buddhist writings like the Mahavamsa and Dipavamsa, as well as commentary on the Tripitaka, contribute to our understanding of the Mauryan period. Later Buddhist writings such as Manjushree Mulakalpa also add to the overall story.

The historical account of the Mauryas is also heavily reliant on Jaina texts. The Kalpa Sutra, Parisista Parva (Hemachandra), and Birhat Katha Kosh are a few of the Kalpa texts that provide important historical context for the Mauryan Empire.

Secular Sources of Mauryan Empire

We can learn a great deal about historical events and socio-political structures from a number of secular sources. For example, Visakhadatta’s “Mudrarakshasha” provides important details about Chandra Gupta Maurya’s rule.

A thorough manual on statecraft and public administration can be found in the “Arthasastra” ascribed to either Kautilya or Vishnugupta. Rediscovered circa 1905 by R. Sama Shastri, the Adhikaran is a Sanskrit text comprising of fifteen books. The Tantra, or first five books, deal with internal administration; the Avapa, or next six to thirteen, books deal with interstate relations; and the last three, or books thirteen through fifteen, deal with various subjects. The authorship and date of the book are still up for debate, though, as Kautilya is not mentioned in other contemporaneous works such as Patanjali’s Mahabhashya and Megasthenes’ Indica, nor is Chandra Gupta Maurya specifically mentioned.

Notwithstanding these doubts, a large number of Indian historians regard the “Arthasastra” as a trustworthy resource for learning about Mauryan governance, social structures, taxation, and economics.

Other secular sources – Patanjali’s “Mahabhasya,” Kalhan’s “Rajtarangini,” and foreign narratives like Megasthenes – are also important in rewriting Mauritius’ history. Even though Megasthenes’ original “Indica” is lost, fragments have survived in later Greek and Latin writings, such as Pliny and Strabo. In their attempts to reconstruct the “Indica,” researchers such as Maccrindle have provided insights into a variety of everyday life topics, such as women’s roles and gold mining, as well as Mauryan society, the caste system, slavery, famines, and municipal administration in places like Pataliputra. In spite of disagreements and objections to reconstructions, the “Indica” is still a useful tool for learning about the Mauryan period.

Final analysis about Indica

Although the “Indica” is an invaluable resource for comprehending historical details, care should be taken when interpreting it. The “double filter” that is always present in this source should be carefully considered when examining how India is portrayed. First, Megasthenes gave his account of events, and then other Greek historians assembled the “Indica” from a variety of quotes, each of which represented their own interpretations. It primarily presents a Greek viewpoint on India, imposing some restrictions on how historical events and subtle cultural aspects are portrayed.

Archeological evidence of Mauryan Empire

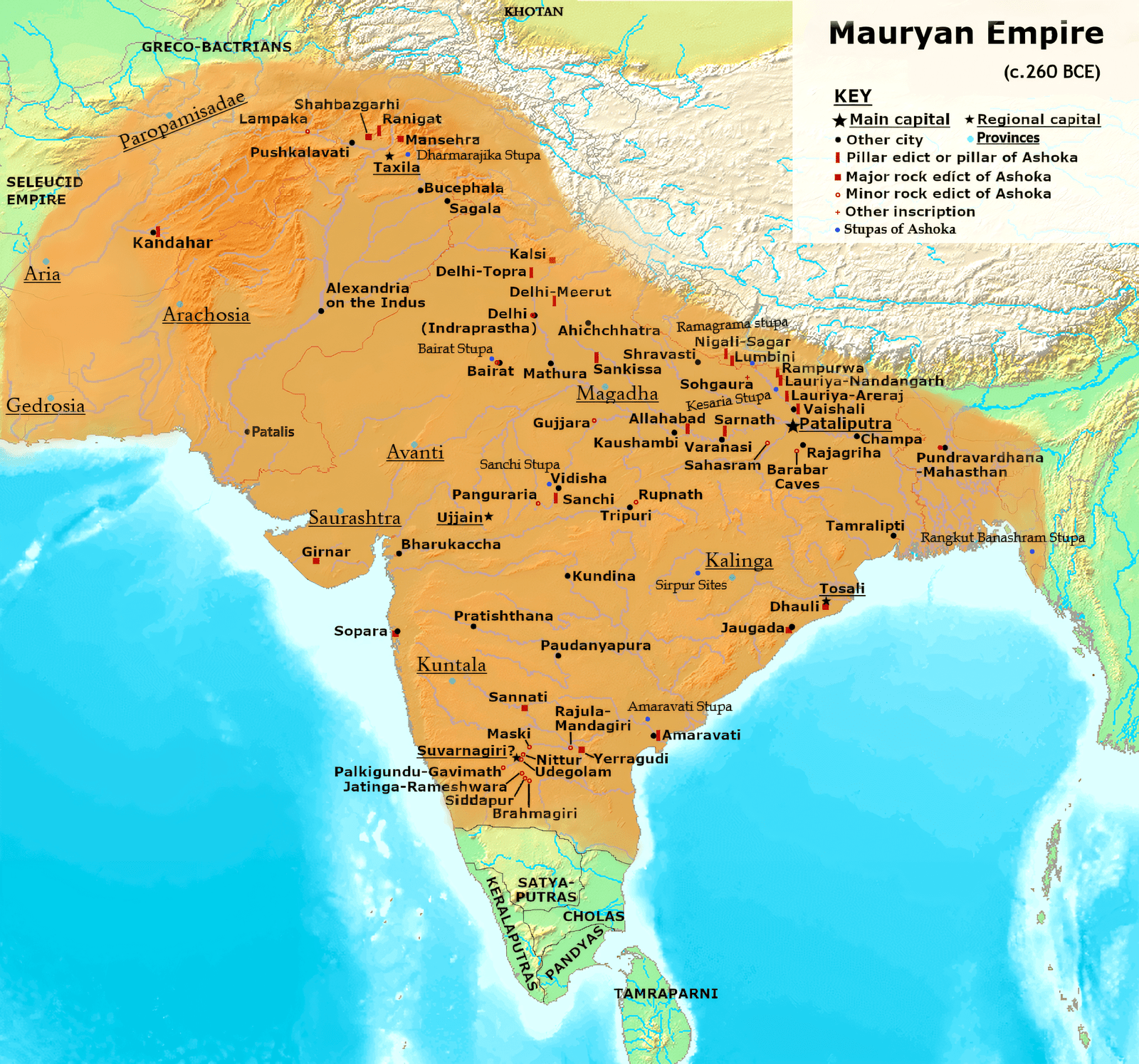

Archaeological evidence—such as sculptures, excavations, and inscriptions—contributes significantly to our understanding of the Mauryan era. Among the notable inscriptions are:

- The Uttar Pradesh Sahagaura inscription,

- The Bengali Mahasthan inscription

- Rudradaman’s Girnar inscription.

Mauryan punch-mark coins also offer important insights: the final coin suggests central authority issuance, and common symbols indicate uniformity. The “Arthasastra” also makes mention of silver coins, or panas.

However, the Ashokan Edicts, which cover a wide linguistic terrain, are the most important sources for the Mauryan period. These inscriptions, which use regional scripts like Brahmi and Kharoshti, are found in the Prakrit, Greek, and Arabian languages.

The decipherment of these scripts by James Prinsep in 1837 signified a turning point in the comprehension of Mauryan history, thus solidifying the Ashokan edicts as an indispensable resource for scholars and researchers.

The Ashokan edicts are categorized into three main types

- Rock edicts.

- Pillar edicts.

- Cave edicts.

Within the rock edict category, there are two subtypes

- Major Rock Edicts (MRE).

- Minor Rock Edicts (MiRE).

Similarly, the pillar edicts are classified into

- Major Pillar Edicts (MPE).

- Minor Pillar Edicts (MiPE).

The Major Rock Edicts are found in various locations

- Mansehara in the Hazara district of Pakistan

- Sehabaz Garhi in Peshawar, Pakistan

- Kandahar in South Afghanistan

- Girnar in Junagarh, Gujarat, India

- Sopara in Thane, Maharashtra, India

- Jaugad in Ganjam, Odisha, India

- Dhauli in Puri, Odisha, India

- Erragudi in Kurnool, Andhra Pradesh, India

- Sannati in Gulbarga, Karnataka, India

- Kalsi in Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India

These edicts, distributed across various geographical locations, serve as crucial historical

markers and provide insights into the policies and principles of Ashoka, the Mauryan

emperor.

Major Rock Edicts (MRE) contain significant information

- underlines that animal sacrifice is forbidden, especially during holidays.

- mention the kingdoms of South India’s south, such as the Pandyas, Satyapuras, and Keralaputras.

- examines important figures, emphasizing the function of Dhammamahamatras.

- brings up Dhamma yatras, which are regal journeys meant to spread moral values.

- documents the victory over Kalinga, a momentous occasion in Ashaka’s history.

Minor Rock edict

- Bahapur (Delhi)

- Bairat (Rajasthan)

- Ahraura (Mirzapur, UP)

- Sahasram (Rohtas, Bihar)

- Gujjara (Datiya, MP)

- Pangureria (Sehor)

- Rupnath (MP)

Karnataka Rock edicts

- Maski (Raichur district)

- Gavimath, (Raichur district)

- Palkigundah (Raichur district)

- Nettur and Udaygolan(Bellari district)

- Rajula Mandagiri and Erragundi(Kurnool district)

- Brahmagiri and Siddapura(Chitradurg district)

- Jating Rameshwara

Major pillar edicts

- Delhi Topra(Ambala district, Haryana).

- Delhi- Meerut(UP)

- Allahabad- Kosam

- Rampurva, Lauriya Nandangadh and Lauriya Araraj(Champaran, Bihar)

Minor pillar edict

- Sanchi(MP)

- Sarnath(UP)

- Varanasi(UP)

- Kaushambi(Allahabad)

- Nigali sagar and Rumindei(Nepal)

- Amravati

Locations where images of Ashokan inscriptions have been identified include the Barabar Caves in Gaya and Kanganhalli in Gulbarga, Karnataka, where cave edicts have been found.

Rulers of Mauryan Empire

Chandragupta Maurya

Numerous accounts, including Greek and Jain accounts, exist about the origins of Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Mauryan dynasty.

Chandragupta was thought to be the son of the Nanda king, with Mura serving as his mother, according to the commentator Dhundhiraj. Hemchandra’s Parisista Parvan, one of the Jain texts, links him to the peacock tamers clan.

In contrast to these stories, the Greek story names him Sandrocottus, who has no royal ancestry. Buddhist writings imply that he is a member of the Khattiya caste. But the conventional wisdom, according to Mudrarakshas, holds that Chandragupta Maurya was of low social standing and humble beginnings.

Chandragupta Maurya rose to prominence in the military by defeating Seleucus Nicator and the powerful Nanda army. He also received notable gifts, such as 500 elephants, and territory concessions.

As per Plutarch, Chandragupta commanded an army of 600,000 soldiers and claimed dominion over the whole Indian subcontinent. In his narratives, Megasthenes emphasized Chandragupta Maurya’s capacity for administration.

Chandragupta Maurya adopted the Ajivika sect as a means of following a spiritual path in his later years. In the end, he decided to follow the severe Sallekhana tradition in Saravanbelgola, Karnataka, which involves fasting until death. This demonstrated a varied and well-rounded life, fusing his military accomplishments with a strong devotion to spiritual activities.

Bindusar

Bindusar, a renowned ruler recognized for his prowess, was also called Amitraghat. The moniker “Killer of Enemies” attested to his combat prowess.

In order to strengthen diplomatic relations, Bindusar even asked Antiochus I, the king of Syria, to send figs, wines, and sophists to his court. His court was notable for having a Greek ambassador in attendance.

Apart from his involvement in politics and diplomacy, Bindusar also showed his spiritual interests by adopting the Ajivika sect. The Tibetan author Taranath claims that Bindusar defeated sixteen states as a show of his military prowess. After Bhuvansar’s death, his son Ashoka became emperor.

Ashoka

After Bindusar’s passing, a dispute over succession emerged. But in his greed, Ashoka killed his 99 brothers in order to take the throne of the Magadhans. Ashoka’s claim was supported by the ministers of the time, who were impressed by his roles as a viceroy in Taxila and Ujjain.

One of Ashoka’s first major triumphs was the Kalinga War, which took place in approximately 261 BC. He was profoundly affected by the great carnage in this conflict, which led to a significant shift in his policies. He gave up on pursuing military conquest and embraced the Dhamma Vijaya philosophy, actively assiduously absorbing Buddhism and propagating its precepts.

Ashoka fostered relations with contemporary rulers like Antiochus Theos of Syria, Ptolemy Philadelphus of Egypt, and Antigonus Gonetus of Macedonia, and maintained direct communication with his subjects through inscriptions. Ashoka started the reforms that were meant to create good governance. But following his passing, the Mauryan Empire began to crumble, with Brihadratha emerging as the final Mauryan emperor.

The breaking of the Mauryan dynasty was expedited by the assassination of Brihadratha by his military commander, Pushya Mitra Shunga.

Mauryan Empire Administration

Kautilya elaborates on the Saptanga theory of the state in his treatise Arthashastra. He calls the Mauryan state a Saptang rajya and the emperor a Chakravarti. According to general texts on ancient Indian polity, the seven essential elements (Saptanga) of the state are ministers (mantri), allies (mitra), taxes (kara), army (sena), fort (durga), land or territory (desh), and an eighth element (shatru), which Arthashastra significantly added.

Kautilya asserts that the king is the supreme authority and is revered as the swami, stressing that the king’s actions should be guided by the Dhamma and the protection of the populace. He highlights the connection between the happiness of the people and the happiness of the king, underscoring the significance of kind governance.

Kautilya underscores the necessity of a council of ministers for effective governance,

asserting that sovereignty is achievable only with their assistance.

Arthashastras mentioned Different kinds of officials

- Mantriparishad Adhyaksha-Head of the Council of Ministers

- Purohita-Chief Priest

- Senapati-Commander-in-chief

- Yuvaraj- Crown Prince

- Samaharta-Revenue collector

- Shulkadhyaksha-Officer-in-charge of royal income

- Koshadhyaksha-Treasury officer

- Dandapala-Head of Police

- Durgapala-Head of Royal Fort

- Annapala- Head of Food Grains Department

- Pradeshika-District administrator

- Akaradhyaksha-Mining Officer

- Lauhadhyaksha-Metallurgy Officer

In addition, the Arthashastra outlines salary guidelines, with a range of 60 to 48,000 panas. The establishment of a distinct vigilance department aimed to supervise and regulate the actions of bureaucrats, guaranteeing responsibility and effectiveness in the administration.

Central Administration of Mauryan Empire

- Provinces

- District

- Village

- City Administration

Provinces Administration of Mauryan Empire

The four or five provinces that made up the administrative structure were each headed by a prince from the Kumar royal line. Senior officials known as Pradeshika were directly appointed by the central government to supervise and control provincial administration in these provinces. The provinces were separated even further into districts called Vishaya or Ahar.

District-level officials, referred to as Rajukas, held administrative positions under the guidance of Yuktas. Gramikas held the position of village head in the villages, which were the smallest administrative units. Additionally, there were intermediary levels of officers, including Gopa and Sthanika, contributing to the hierarchical organization of the administrative system.

City administration of Mauryan Empire

Megasthenes claimed that the city was divided into different wards, each under the direction of a commission composed of thirty people whose job it was to administer the city. Six committees, each with five members, were formed out of this commission. These committees were in charge of various facets of local government,

- One committee looked after industries.

- The second committee looked after foreigners.

- The third committee looked after the registration of birth and death.

- The fourth committee, looked after the trade.

- The fifth committee looked after manufacturing and sales.

- Six committees looked after tax collection.

Judicial Administration of Mauryan Empire

The King was the highest judicial authority in the field of judicial administration. Two types of courts were mentioned when they were established in major towns to administer justice.

First of all, Dharmasthiya courts handled civil cases mostly involving inheritance and marriage. These courts, which consisted of three judges knowledgeable in sacred law and three matyas (secretaries), were essential to settling civil disputes.

Second, the Kantakashodhan courts, which were also led by three Matyas and three judges, were very important. Their main goal was to get rid of various crimes and anti-social elements, much like modern police do. A network of spies was heavily relied upon by these courts to obtain information regarding such activities. The penalties imposed for transgressions were frequently harsh.

The overarching goal of the judicial system was to expand governmental influence over

various facets of ordinary life, emphasizing control and order in society.

Mauryan Empire Administration of the Army

A standing army with distinct officials was maintained in compliance with the Arthasastra. Greek records mention the existence of a thirty-member council that was split up into six committees, each in charge of particular military tasks:

- The first committee oversaw the Navy.

- The second committee managed Infantry.

- The third committee managed Cavalry affairs.

- The fourth committee focused on War Chariots.

- The fifth committee handled matters related to War Elephants.

- The Sixth committee was responsible for overseeing Transport logistics.

Mauryan Empire Regulation of Economic Activities

Land, and specifically land revenue, was the state’s main source of income. Bhaga, the royal entitlement, made up one-sixth of the total produce. The Rummindei Inscription demonstrates Ashoka’s reduction of some regions to 1/8. Land tax collection was left to a group of government employees known as Agrohomai.

The state received income from a number of sources in addition to land revenue, such as trade taxes, forest taxes, alcohol levies, emergency taxes, irrigation taxes, and the like.

Agriculture in Mauryan Empire

By encouraging people to settle in new areas and increasing the amount of land under cultivation, the state actively promoted agricultural development. Shudra settlers were given financial incentives in the form of supplies like seeds to help them establish new settlements on undeveloped land. Slaves from heavily populated areas were brought in to augment the labor force for cultivation, which improved agricultural productivity.

Textile Manufacturing in Mauryan Empire

The state was instrumental in the development of the ivory, leather, and pottery industries and actively promoted textile manufacturing. Writers like Arien and Niyarchus claim that this was a prosperous time for Indian industry.

The flourishing of internal trade was made possible by the state’s provision of peace and security. Traders were raised and developed close ties with the outside world.

Buddhist sources described caravan traders who shipped large amounts of cargo to far-off places.

Waterways such as Tamralipti and Sopara were systematically developed, adding to the expansion of trade routes in addition to the overland trade.

Nature of the Mauryan Empire

Based on insights from the Arthashastra, Romila Thapar initially described the Maurya Empire as highly centralized. But in 1980, historians like Gerard Fussman brought up issues that called into question this viewpoint. As a result, Thapar revised her position and suggested that the Mauryan Empire was a collection of various political, economic, and cultural components rather than a single, homogenous entity.

Thapar presented the idea of the Mauryan Empire, which included core regions, peripheral zones, and metropolitan areas, in opposition to the idea of high centralization. She highlighted the many different and distinct governance structures that existed within the empire, as well as the extensive delegation of authority that existed within it.

Conclusion

Although this view has been contested, traditional perspectives described the Mauryan Empire as a centralized bureaucratic entity. For example, Upinder Singh contests the need to define the Mauryan Empire as strictly “centralized” or “decentralized.” According to Singh, the empire probably had some centralized control, but because of its size, officials at the provincial, district, and village levels would have also had a significant amount of authority.

Religion in the Mauryan Empire

Buddhism and Jainism were highly influential during the Mauryan era.

The Prakrit word “Dhamma” is the Sanskrit word “Dharma” in form.

Regarding Ashoka’s Dhamma, different people have different opinions. R.G. Bhandarkar said it wasn’t a type of secular Buddhism, while R.K. Mukharjee said it was more of a moral code than a religious system.

Many historians today interpret the Dhamma as a type of global religion. Frequently understood as “Raj Dharma,” it emphasizes a code of morality and ethics over a dogmatic religious doctrine. This nuanced interpretation is consistent with the theory that the Dhamma encompassed a larger set of principles that extended beyond the boundaries of a particular religious framework.

Why this policy

Political pressures and the circumstances of his time led to the acceptance of these concepts. Romila Thapar talked about the advantages of adopting these ideas.

Features

It emphasized particular moral precepts but did not give an explicit definition. The pillar edicts of Ashoka attest to the Dhamma’s explication of virtues like kindness, respect, and a steadfast commitment to moral behavior. It promoted the reduction of immoral behavior and the elevation of good deeds, stressing virtues like kindness, generosity, sincerity, and purity. The central idea was ahimsa, or non-violence, which exhorted people to abstain from anger, cruelty, and pride. Dhamma was understood as a moral duty in this setting.

Outcome

No long-term result. According to Romila Thapar: It didn’t provide a long-term solution. While it was very important, it was unable to provide a long-term solution and only contributed to the empire’s brief survival.

Causes of the Decline of the Mauryan Empire

- H.P. Shastri proposed that brahmanical reactions resulted from Ashoka’s religious policy, which favoured Buddhism and allegedly marginalised Brahmanism. However, this perspective is not widely accepted and lacks evidence of widespread Brahmanical opposition.

- Despite the army being maintained, H.C. Ray Chaudhary claimed Ashoka’s policy of non-violence weakened it, which is why he attributed the decline to it.

- Dr. Kaushambi contended that high military and bureaucratic spending led to a financial crisis.

- Romila Thapar called attention to the administration’s extreme centralization, calling it “top-heavy,” and expressed her belief that it was unsustainable.

- Dr. R.K. Mukharjee concluded that the decline was partly caused by repeated uprisings in the provinces.

- The collapse of the Mauryan Empire was caused by a number of other factors, including the neglect of the North-West frontiers and susceptibility to foreign invasion.

Pre & Mains : Buy History NCERT 11th class by R.S.Sharma for UPSC

History Optional : Buy A History of Ancient And Early Medieval India : From the Stone Age to the 12th Century By Upinder Singh

Featured image credit :- creative commons

Wow, detailed map ..even Ashoka Stupa are also mentioned… Point wise summarised topics.

Good summarised written article.