Origin & the Rise of Rajputs

The term ‘Rajput’ finds its roots in the Sanskrit word Rajputra, initially signifying the “son of the king.” But its use in literary texts changed as early as the 7th century CE, when it began to denote a landowner or noble rather than a direct descendant of the king. It is used in Banabhatta’s Harshacharita to refer to a noble or land-owning chief. The 12th century saw the beginning of its more common usage, which frequently alluded to the 36 clans.

Rajaputras are described as making up a significant portion of chief-holding estates, each of which is in charge of one or more villages, in Bhatta Bhuvanadeva’s Aparajitapriccha.

The fascinating historical account of the Rajputs’ emergence and rise begins with the fall of the Gupta Empire in the sixth century CE. This warrior clan became well-known for its valor, chivalry, and martial prowess. It was centered in the northwest of what is now Rajasthan, Gujarat, and portions of Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh.

There are numerous factors that have contributed to the Rajputs’ rise to power. First of all, the fall of the Gupta Empire created a power vacuum that gave local leaders and clans—including the Rajputs—the opportunity to seize control and found kingdoms. Second, the Rajputs’ military prowess—especially in mounted combat—was a key factor in their victory. They are exceptional fighters because of their bravery and military prowess.

Their position was further strengthened with the adoption of the Rajputana code, which placed an emphasis on honor, loyalty, and courage. This helped to maintain regional dominance and facilitate the formation of alliances. Their economic power and agrarian stability were also influenced by their geographic advantages, which allowed them to control important trade routes and agricultural lands.

The Rajput dynasties, which included the Chauhans, Rathores, Solankis, and Kachwahas, exerted a notable influence on the political and cultural milieu of medieval India. Despite times of strife and rivalry between the various Rajput clans during their ascent, their collective bravery, artistic contributions, and architectural accomplishments made a lasting impression on Indian history.

Foreign origin theory

According to the foreign origin theory, Rajputs are the descendants of outside invaders who eventually blended into Hindu culture. Diverse historical viewpoints suggest that the Rajputs have distinct foreign ancestries.

Colonel Tod suggested a lineage traced back to the Shakas, while Sir Alexander Cunningham suggested they were descended from the Kushanas. Jackson proposed that the Rajputs might have descended from the Khajar clan in Armenia, a theory that has been supported by some academics.

Several academics agree that the Rajputs are descended from a variety of foreign groups, including the Shakas, Kushanas, and Hunas. According to this theory, the Rajputs arrived as foreign invaders but eventually assimilated into Hindu society, presenting a nuanced historical account.

Tribal Origin Theory

Certain historians posit that the Chandela dynasty has its origins traced back to the

Gond tribe.

Agni kund Theory

Certain Rajput clans are identified as Agni Kund Rajputs by the Agni Kund theory, which is based on popular belief and is referenced in Chandabardai’s Prithviraj Raso, a book connected to Prithviraj Chauhan’s court. This theory holds that Chauhan, the Chalukyas of Gujarat, Parmar, and Pratihar, who can trace their ancestry back to the Agni Kund, are the original Rajputs.

Theory of Descent from Kshatriyas

According to the theory of descent from Kshatriyas, which gained popularity thanks to Gauri Shankar Ojha, Rajputs are descended from a historical Kshatriya lineage. Ojha provides strong evidence in support of this assertion by citing Puranic texts and the historical background of Kshatriya families. Many historians came to agree with this theory.

theory of origins among the Brahmans.

Majumdar, R.C. had a theory that was well-supported by evidence. He thought that the original Brahmin caste included figures like Hindushchandra and the Gurjar Pratihara.

According to Dashrath Sharma, a lot of Rajput families were originally Brahmin families.

Sharma claims that Brahmanas became warriors and began referring to themselves as Rajputas because of the uncertain times.

However, these ideas had some drawbacks. In a more recent viewpoint, B.D.

Chattopadhyay suggested the “processual theory,” saying that Rajputs didn’t suddenly

appear in politics; it happened gradually. Chattopadhyay also accepted the Theory of

mixed origin as a reasonable explanation for the Rajput lineage.

Theory of Mixed Origin

According to the Theory of Mixed Origin, a number of powerful land-owning families started referring to themselves as Rajputs over time. It’s possible that they made this change to justify their status. It is believed that the Rajput identity was adopted as a reaction to the unpredictability and instability of the current social and economic landscape.

Paramars

They were known as Rajputas and ruled the Malwa region, serving as vassals to the Rastrakutas. We are looking for more information about their origins. Upendra, popularly known as Krishna Raj, was the first historical king, and their capital was Dhar. After Upendra, Siyaka II is recognized as the true founder. The inscription on Harshola’s copper plate showcases his achievements.

Famous fighters like Munj and Sindhu Raj subsequently took on crucial roles. The most notable of their kings was Raja Bhoja.

Raja Bhoja

Raja Bhoja was well-known for his extensive knowledge and support of education. He wrote over 23 books, including the Samranga Sutradhar and a commentary on Patanjali’s Yogasutra. Approximately 500 scholars, including Dhan Pala and Uvata, were present in his court.

He is also credited with founding the city of Bhojpuri and building several temples, one of which is the Sarasvati temple. Dhar prospered as a literary and cultural hotspot during his reign.

Bhoja’s academic achievements, rather than his military prowess, are what define his legacy.

After his death, the reign of the Paramar emperors ended.

Cholas

Vijayalaya is credited with founding the imperial Cholas when he overthrew the Muttaraya chief and made Tanjore the capital. The next in line, Aditya Chola, defeated the Pallava emperor after him.

Parantaka I overthrew Aditya Chola and defeated the Pandyas and Rastrakutas. Under Rajaraja I, the Cholas regained power in 985 AD, defeating the weaker Pandyas, Cheras, Mysore, Northern Sri Lanka, and the Maldives Islands.

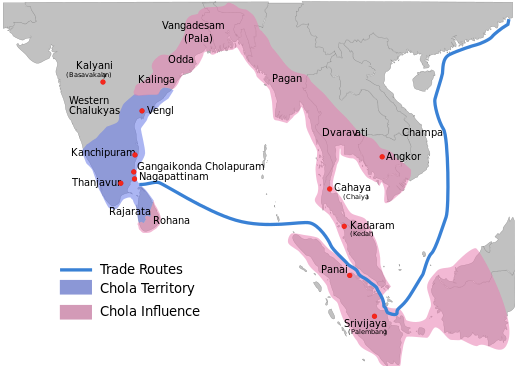

By annexing all of Sri Lanka and assuming authority over the Cheras and Pandyas, Rajendra I increased the Chola dynasty’s power. He is renowned for his Southeast Asian expeditions, and his military even crossed the Ganga River.

South India bears the permanent imprint of the Chola dynasty, which flourished from the ninth to the thirteenth centuries CE. The Chola dynasty reached its peak under Rajaraja Chola I and his son Rajendra Chola I, who expanded the empire over what is now Tamil Nadu, portions of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, and northern Sri Lanka.

The Cholas, who were well-known for their strong naval might and commercial connections, carried out a great deal of maritime commerce and developed diplomatic relationships with countries in Southeast Asia.

Famous temples such as the Brihadeeswarar Temple in Thanjavur serve as testaments to their architectural prowess, and their cultural contributions are demonstrated by their patronage of literature and art, which includes the well-known Chola bronze sculptures.

The decline of the Cholas commenced after the rule of Rajendra III, marking the end

of their illustrious dynasty.

One of the long-lasting ruling families in the area was the Chola dynasty, which ruled over a large portion of South India from the ninth to the thirteenth centuries. The Chola dynasty reached its pinnacle under the distinguished leadership of Emperor Rajaraja Chola I and his successor, Rajendra Chola I. The Cholas, who were renowned for their remarkable naval prowess, vast trade routes, effective administration, and passionate support of the arts and architecture, left a lasting impression on the history of South India.

Notably, the Cholas were essential in spreading Tamil culture and Hinduism throughout Southeast Asia. Modern-day Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Sri Lanka were all part of their enormous empire. The Cholas’ contributions to South India’s political climate, cultural legacy, and architectural wonders demonstrate their lasting influence.

Chola Administration

The monarch was positioned at the head of the Chola Administration. Mandalam, which was further divided into Valanadu, Valanadu into Nadu, and Nadu into villages, was part of the organizational hierarchy of the empire. Notably, there was some autonomy enjoyed by local government.

The king was referred to by a number of titles in Chola inscriptions, including Ko, Perumal, Adigal, and Ko-Konmai Kondan, indicating his elevated position as the ruler of rulers. It was common to compare the monarch to a deity. The king is described as having a pleasing physical appearance in Chola inscriptions, which also show him to be a devoted patron of the arts and a fearsome warrior.

The Cholas were thought of as protectors; Marco Polo even proposed an unusual custom for funerals: the king’s bodyguard would self-immolate when he passed away. This demonstrates the great regard and allegiance that the Chola king inspired and highlights their significant influence on politics and public opinion.

What was the Chola kingship theory

It is possible to comprehend the Chola kingship theory by looking at their rituals and purported ancestry.

The Cholas claimed descent from the Suryavansha lineage, a claim supported by inscriptions detailing the king’s genealogy found on the Tiruvalangad copper inscription and the Anbil plate inscription.

The Cholas, who considered themselves members of the warrior class known as Kshatriyas, used a variety of strategies to prove their legitimacy. They performed rituals like the Hiranyagarbha sacrifices, which served as a symbolic confirmation of their noble ancestry and reaffirmed their position as rulers. By giving their claim to be descended from the illustrious Suryavansha lineage a cultural and religious backdrop, these customs played a crucial role in supporting the Chola kingship theory.

Elaborate Administration machinery

Historical records demonstrate the intricate administrative machinery of the Cholas.

A clear bureaucracy was created, and Raja Raj is credited with its initial growth. This administrative framework persisted until Kulottunga I’s rule.

An important role was played by a much higher official in this system, called Perundanam. Lower-level officials, or serundanam, were also essential to the administrative structure and complemented this. The aforementioned evidence highlights the Cholas’ dedication to a well-structured governance framework, exhibiting the hierarchical configuration of officials accountable for the efficient operation of their administration.

Elaborate military administration

While in combat, the Cholas maintained an all-encompassing military government.

There was a standing army with infantry, cavalry, naval, and elephant units that were meticulously maintained. Roughly seventy regiments are known to have existed historically, demonstrating the size and configuration of their armed forces.

Within the Chola military, loyalty was deeply ingrained, with devoted soldiers playing a vital role. Specialized troops known as Valaikarar formed a close-knit unit under the king’s protection. A military cantonment known as Kadgam is mentioned, which sheds light on the infrastructure and strategic planning that underpin Chola military operations.

Comprehensive narratives elucidating the composition of the army and the function of bodyguards illuminated the painstaking planning that went into Chola military operations. Notably, realizing the navy’s strategic importance, the Cholas gave it special attention. This thorough approach to military management demonstrates the Cholas’ dedication to upholding a strong and efficient defense system.

land revenue system

During the Chola era, a well-organized land revenue system was in place, overseen by the Puravuvarithinaikallam land revenue department.

Different land types were identified and carefully surveyed, resulting in a classification for evaluation. These land categories are described in detail in Chola inscriptions.

Known as “kadamai,” the land revenue usually amounted to one-third of the produce.

The Cholas established a vast tax collection system that included about 400 different kinds of land taxes.The two main forms of taxes found in Chola records were kaddamai, which represented land revenue, and vetti, which was collected as forced labor instead of cash.

In addition, there were levies on a number of activities, including thatching homes, climbing palm trees with a ladder, and acquiring family property through inheritance. In addition to these, professional taxes were also levied.

This complex system of land revenue and taxation demonstrated the Cholas’ careful handling of economic matters throughout their rule.

Type of land:- We have different categories of land.

| Category of Land | Description |

| Vellanvagai | Land of non-Brahmana peasant proprietors |

| Brahmadeya | Land gifted to Brahmanas |

| Shalabhoga | Land for the maintenance of a school |

| Devadana, tirunamattukkani | Land gifted to temples |

| pallichchhandam | Land donated to Jaina institution |

The organizational structure of the Chola state consisted of splitting the state into mandalams, which were then further subdivided into valanadu and nadu. Royal princes were in charge of the mandalams; Periyanattar was in charge of Varanadu, while Nattar was in charge of Nadu.

There was a unique system in place for city administration, with Nagarattar in charge of Nagaram.

Nadu, on the other hand, was split up into a number of villages, each with its own distinct administrative structure that permitted regional autonomy. The villages were divided into three categories: Ur, Sabha, and Mahasabha. The villages in Sabha and Mahasabha were predominantly Brahminical.

The village was split up into 30 wards, each of which had a designated representative, for a total of 30 members. These individuals formed six committees, or variyams, each with five members that were in charge of various administrative responsibilities. Detailed insights into this elaborate village administration system during the Chola period can be found in the Uttaramerur inscription.

Who could be a member of a sabha? The Uttaramerur inscription lays down

- All those who wish to become members of the sabha should be owners of the land from

- which land revenue is collected.

- They should have their own homes.

- They ought to be in the age range of 35 to 70.

- They ought to be familiar with the Vedas.

- They ought to be trustworthy and knowledgeable about administrative issues.

- A person is not eligible to join another committee if they have served on any committee within the previous three years.

- Those who have not filed their accounts, or those of their kin, are ineligible to run in the elections.

Nature of Chola state

Various viewpoints among historians regarding the characteristics of the Chola state have led to divergent beliefs. One widely held belief, supported by academics such as P. B. Mahalingam, Nilakantha Shastri, and Minakshi, describes the Chola state as a centralized monarchy. It was specifically called a centralized model by Nilakantha Shastri.

But in his book “Peasant State and Society,” published in the 1980s, Burton Stein criticized this centralized approach and put forth the segmentary state model. A segmented state, in Stein’s view, demonstrates both political and ritual sovereignty. While the king directly governs the central region of the kingdom, peripheral areas see the cooperation of Brahmins and dominant peasants, leading to centralization only at key locations.

On the other hand, the segmented state theory was rejected by Professor Noboru Karasima of Japan, who argued against the alliance between Brahmins and peasants. He criticized Stein for his clumsiness in elucidating ritual sovereignty and highlighted the diverse makeup of the peasantry.

D. N. Jha provided an alternative interpretation of South India’s history by using a feudal model.

Historian George Spencer offered the notion that the Chola state was a “plunder state,” presenting the idea of plunder as a distinguishing feature.

Considering these divergent perspectives, it is still difficult to come to a definitive conclusion about the nature of the Chola state.

Socio-Economic Life of Cholas

The caste system was the foundation of the dominant social structure during the Chola era. The status of the Pariyars, or untouchables, was appalling, while the Brahmins and Kshatriyas enjoyed special privileges. Though not significantly, Shudras saw some improvement, especially for landholders.

The separation of Chola society into Valangai and Idangai was one of its distinctive features. Farmers made up the left-hand group, the Idangai, and artisans and craftsmen made up the Valangai, or right-hand group. These two groups worked together at first, but eventually tensions developed between them.

Brahmins received land grants and royal support, which improved their social standing, especially as a result of the expansion of temples. However, as demonstrated by customs like the Devadasi system and Sati, women’s conditions did not significantly improve.

Shaivism became the most popular religion during this time. The growing influence of temples on politics, the economy, education, and society was an interesting aspect. Temples were important in many facets of Chola’s life, representing the complex interactions between social, religious, and economic factors.

Temple Economy

DN Jah first used the term “Temple Economy” to describe the Chola civilization’s economic structure. Through the establishment of irrigation projects and the expansion of cultivable land, temples were instrumental in the growth of the agrarian economy. They supported handicrafts and other artistic endeavors, acted as financial intermediaries by helping businesspeople arrange loans, and were crucial to the growth of markets—they even acted as market hubs that aided in the emergence of urban centers.

Temples enjoyed a good reputation in the Chola economy because of their various contributions, which gave them a positive character. They were not only important actors in the economy, but they were also instrumental in advancing trade-related endeavors.

Temples served as marketplaces, promoting trade and business that fueled the development of urban areas surrounding them. They continued to play a major role in the Chola economy and were essential to economic activity. In addition to being well-known for their contributions to agriculture, the Cholas made significant contributions to the growth of industries and crafts.

The idea of the Temple Economy essentially captures the various and significant roles that temples had in influencing the Chola civilization’s economic environment, from the growth of agriculture to the encouragement of trade and the creation of crafts and industries.

Craft and Industry

The Chola era was recognized for its thriving textile industry, with Kanchi becoming a major hub for silk weaving. During this time, metalworks also flourished and produced a variety of coins, one of which was the well-known Kashu.

The Chola civilization maintained strong trade ties with nations outside of its borders, including China, Southeast Asia, and Arabia. Notably, there were regular interactions with the outside world, as demonstrated by the significant importation of Arabian horses.

Nagaram, which was unique to various trades, was a sign of the well-established internal trade within the Chola civilization. Saliya Nagaram is associated with the textile trade, Shankar Padi Nagaram with oil-related activities, and Paragmagram with seafaring merchants are a few examples.

Guilds played a crucial role in this economic landscape, functioning as autonomous

corporate organizations within the same craft. Referred to as Shrenis and Pugas,

these guilds, such as the ‘Ayyavole’ (also known as the “500 Swami of Aihole”),

extended their influence beyond South India. Two distinct types of guilds emerged

during this period: ‘Ayyavole’ and ‘Mani gramman.’ Additionally, trade guilds known

as Anjuvannam evolved, emphasizing the significance of trade and commerce during

the Chola era.

Cultural achievements of the Cholas

Architecture

The inception of Dravidian architecture took place during the Pallava period,

reaching its peak maturity during the Chola era when Dravidian temples were

extensively developed. These temples exhibited distinctive features:

- Vimana: The Vimana, a pyramid-shaped tower, represented a complex structure.

- Fortification: Temples were often fortified.

- Mandapas: Numerous assembly halls, or Mandapas, were integral components.

- Gopuram: The entrance gateways, known as Gopuram, were grand and imposing.

- Temple Tank: Temples included a designated area for a temple tank.

- Devalayas: Subsidiary shrines called Devalayas adorned the temple complex.

- Vahanas: Vahanas, such as the Nandi, symbolized the deity.

- Garbha Griha: The inner sanctum, or Garbha Griha, housed the primary deity.

- Pradakshina Path: Temples incorporated a circumambulatory path.

- Decorations: Dravidian architecture featured decorated walls and sculptures, including Dwarpalas.

Some Dravidian temples even featured Dwarpalas. The primary structure was

referred to as Mula Prasad, while subsidiary structures were known as Devalayas. The

Antarala served as the connecting link between the Garbhgriha and Mandapa.

Examples of Chola temples showcase the evolution across different stages:

Ancient Temples: The Vijayalaya Choleshwar Temple in Narthamalai represents a connection to the Pallavas and was an early temple.

Mature Temples: One of the best examples of a well-developed Chola temple is the Brihadeshwar Temple in Thanjavur.

Late Temples: The Airavateshwar Temple in Darasuram is an illustration of a late Chola temple.Together, these temples represent the development and distinctive qualities of Dravidian architecture, which reached its zenith during the Chola era.

Sculptures and Literature

The Cholas became well-known for their magnificent bronze sculptures, one of the most well-known of which is the famous Natraj sculpture. Natraj is a deep illustration that captures the spirit of Indian philosophy.

The Chola era saw notable advancements in painting as well as sculpture, especially on temple walls. The Cholas were renowned for their contributions to Tamil and Sanskrit literature as well.

Prominent literary compositions from the Chola period encompass the archetypal Chola literary work, “Sibka Sindamani.” Kamban also made a major literary contribution during this time with his Tamil Ramayana. “Kalingatuparni,” written by eminent scholar Jayagondar, added to the era’s rich literary canon.

Academics connected to the Chola court, like Kutton and Puglendi, were prolific writers who produced a large body of work. Significant literary advancements occurred during this time, and Shaivism and the Tamil bhakti tradition continued to be major themes.

The Cholas were significant in promoting Tamil bhakti traditions in addition to being well-known for their contributions to Sanskrit literature. Thus, the Chola period is remembered as a noteworthy period in Indian history, marked by innovations in literature, painting, and sculpture that capture the intellectual and cultural vitality of the day.

Pandyas

During the Sangam era, Pandyas were influential, but their numbers decreased in the Kalabhra era. Madurai was always referred to as Kudal in Tamil classics.

According to the inscription found in the Vaigai river bed, the Pandya dynasty experienced a resurgence in the seventh century AD, particularly during the rule of Arikesari Maravarman.

The Cholas posed a threat to the Pandyas, which diminished their power. Following the Chola dynasty’s decline in the 13th century, the Pandyas underwent a remarkable comeback and became one of Tamil land’s most influential dynasties.

Marco Polo recognized the strength of the Pandyas during his visit in the thirteenth century, when figures such as Sundar Pandya, Kulasekhara, and Vir Pandya were becoming more well-known.

However, the invasion by Malik Kafur during Alauddin Khilji’s period dealt a severe blow to the Pandyas, resulting in the plunder of their territories and contributing to their overall decline. Notwithstanding these difficulties, the Pandyas were instrumental in maintaining Tamil culture during their historical odyssey.

Pre & Mains : Buy History NCERT 11th class by R.S.Sharma for UPSC

History Optional : Buy A History of Ancient And Early Medieval India : From the Stone Age to the 12th Century By Upinder Singh

Inline image credit :- wikimedia Commons license

Featured Image Credit and License :-

This image was first published on Flickr. Original image by Jean-Pierre Dalbera. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution. This license lets others distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon your work, even commercially, as long as they credit you for the original creation. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms